Passing the (climbing) grade

This past weekend, I had the chance to climb at the New River Gorge, one of the best climbing destinations on the East coast (and probably the closest world-class crag to where I live). Unfortunately, I’m rehabbing a wrist injury, so the hardest climb I got on was graded 5.9, several notches below the level I’m trying to climb at consistently. Fortunately, it was the classic epic 80-foot Flight of the Gumby.

Climbing grades are imperfect and possess an element of subjectivity – climbers from different regions and generations may have different ideas of how difficult a particular grade “feels”. Nonetheless, climbing grades are the standard most climbers use to gauge their progression. I recently found and cleaned some climbing data scraped by David Cohen.

The dataset

The dataset records ascents logged by climbers on 8a.nu – containing the climb’s grade, and various details about the climb and the climber. I excluded climbs graded easier than 5a (based on the French system), as anything lower is nothing more than walking up a ladder. This left over 4 million climbs logged by 35,799 users. Most users only had a few climbs logged, but a small portion logged over 1,000 climbs (n = 368).

Because of the variation in the number of climbs across different climbers, treating each logged climb as an observation could be misleading. Instead, I’ll focus on each climber’s “ceiling” – the hardest grade climbed. This ensures that each climber is associated with a single observation.

Distributions of ceilings

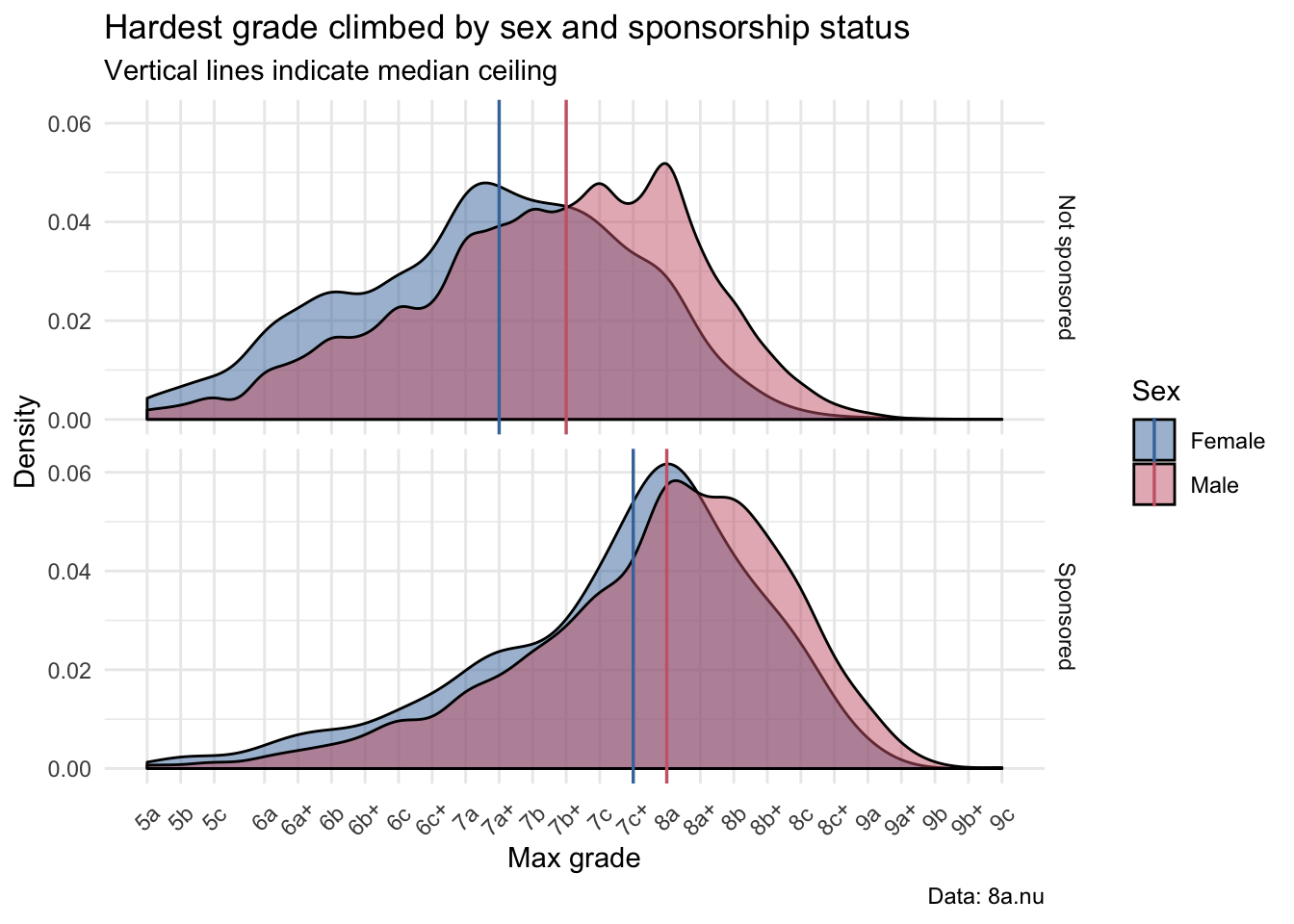

I plotted the distribution of ceilings to see if there are sensible differences between groups. The following density plot shows these distributions (normalized, as there are imbalances in the number of climbers within each group in the dataset). The vertical lines indicate the median of each distribution.

Comparing the distributions in the bottom vs. top plot, climbers with at least one sponsor (“sponsored”) have higher ceilings (median ceilings of 7c+ and 8a for females and males, respectively) than those who are “not sponsored” (median ceilings of 7a+ and 7b+). This is a pretty obvious finding; climbers with sponsorship are likelier to climb at a higher level, and also have more time to climb.

In both plots, male climbers have slightly higher ceilings on average than female climbers. However, this difference between male and female climbers’ ceilings is greater amongst climbers who are “not sponsored” (two grades) compared to those who are sponsored (only one grade). This suggests that female climbers who obtain sponsorships are especially strong relative to other female climbers.

Survival up the grade ladder

Survival analysis is a branch of statistics used to analyze the duration of time to an event, and the factors that influence those durations. For example, in a series of cancer patients, survival analysis would be used to figure out the probability of patients surviving for three years, and also if there are differences in survival times between patients undergoing different treatments.

If a climber reaching his or her ceiling represents the event of interest, then easier grades, like a ladder leading up to the ceiling, could be viewed similarly to the time leading up to an event.1 This allowed me to ask questions about the probability of a climber obtaining a ceiling of 7b+, and if there are differences in ceilings between different groups of climbers.

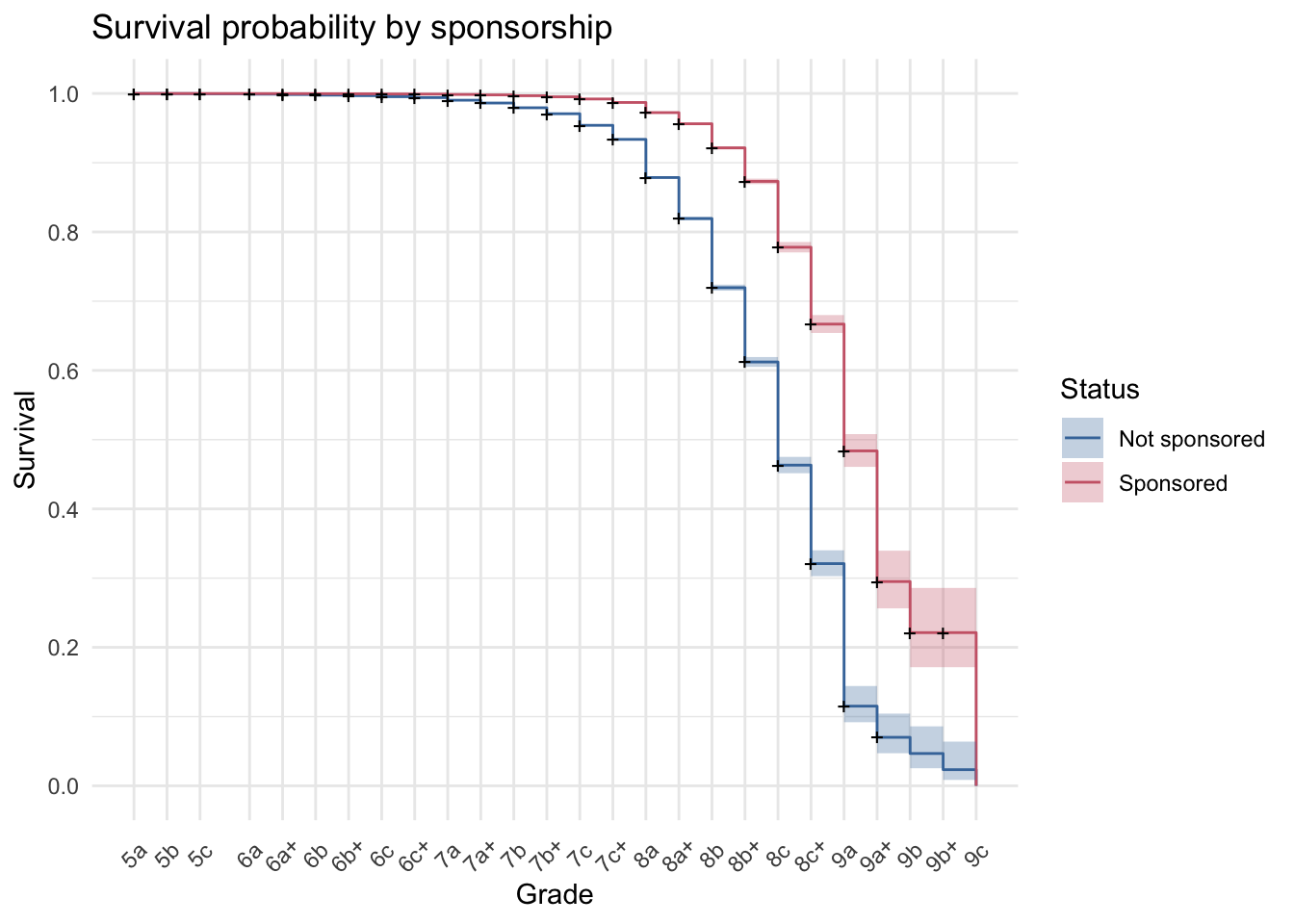

Using the survival package in R, I generated the following survival plots to visualize how sex and sponsorship status influences the ceiling that climbers obtain (mirroring the plot of distributions in the prior section).

The first plot visualizes the probability that a male or female climber in the dataset will still be able to complete climbs of a particular grade. The second plot visualizes the probability that a sponsored or non-sponsored climber in the dataset will still be able to complete climbs of a particular grade.

A Cox proportional hazards model can be used to compare the relative risk of reaching one’s ceiling between different groups. There is a lower risk of a male climber reaching a particular ceiling relative to a female climber reaching that ceiling; hazard ratio, HR = .39, 95% CI [.39, .40].2 There is also a lower risk of a sponsored climber reaching a particular ceiling relative to a non-sponsored climber; HR = .21, 95% CI [.21, .22]. These results confirm what is visually apparent in the plots above.

Guess who?

I figured it would be interesting to look at potential differences between climbers from different countries. Unfortunately, that becomes unwieldly because there are 162 countries represented in the dataset. I created a survival plot featuring the six most represented countries in the dataset (USA, Spain, Poland, Germany, Italy, and France), plus the Czech Republic.

Guess who shows up with the highest ceiling, making the Czech Republic an outlier? The dataset is anonymized, so I can’t see the climber’s name, but any climber should recognize the distorting outlier that is Adam Ondra.

Next ascents

This is a very preliminary look at climbing data, but there are obviously more interesting questions and fine-grained analyses that can be done. For example, having records of multiple ascents by each climber would allow a look at the rates of progression through different grades, and the factors that are related to faster or slower progress.

If anyone (especially climbers) have ideas for further analyses and potential collaborations related to this dataset or similar data, I’d love to hear from you (see links in sidebar). Until then, I’ll be back to climbing as much as I can.

In traditional survival analysis, an event like a patient dying at a particular point in time implies that the patient is still alive at all preceding points in time. Using an ordinal variable (climbing grade) in place of time is a non-traditional application. I drew the analogy because having a ceiling at a particular grade (the event) implies that a climber can climb at all grades preceding it (i.e. has not yet reached her ceiling).↩

A hazard ratio = 1 indicates the likelihood of the event occurring is the same across both groups, while HR < 1 or > 1 indicates that the likelihood of the event occurring is greater in one group.↩